Any Neil Young record was never going to be a walk in the park to pull off. Young was never content to rest on his laurels and deliver the kind of album everyone wanted to hear, and once he had his fill of a specific genre, he was finished and ready to move on to whatever genre sparked his interest next. That may have made for a PR nightmare whenever he started working on some of his weird genre experiments, but as far as Young was concerned, the corporate side of rock had no idea what it wanted.

After all, Young had spent the lion’s share of the 1970s doing what he wanted, and even when it was a little bit disheveled, like on Zuma, it was hardly a bad thing. Hell, Tonight’s the Night is littered with mistakes all throughout its track listing, but since Young was dealing with leaving behind essential members of Crazy Horse, making an album that sounded this frail was exactly the right approach.

But that no-nonsense outlook in the studio was never going to work once the 1980s kicked into high gear. No other artist was ever less equipped for MTV than Young, and while he was usually fine with making records to piss off his record company, like Everybody’s Rockin’, the lack of sales meant that he had to seriously consider what his next move was going to be. And while he did at least try to make something trendy, that ended up going even worse than him following his muse.

His country records were never going to sell as well as in the age of neon-colored spandex, but listening to what he did on albums like Landing on Water or his return to Crosby, Stills, and Nash in the late 1980s, he was slowly starting to become a relic of the past in many people’s eyes. That is, until the grunge movement came in using his exact same musical aesthetic.

Since Young also returned to form with Freedom in the early 1990s, he was starting to become a lot cooler again. His need to do what he wanted regardless of what the label said was practically the mantra of the Seattle scene, but when he made an album with Pearl Jam, he had no problem being blunt about what the grunge scene represented.

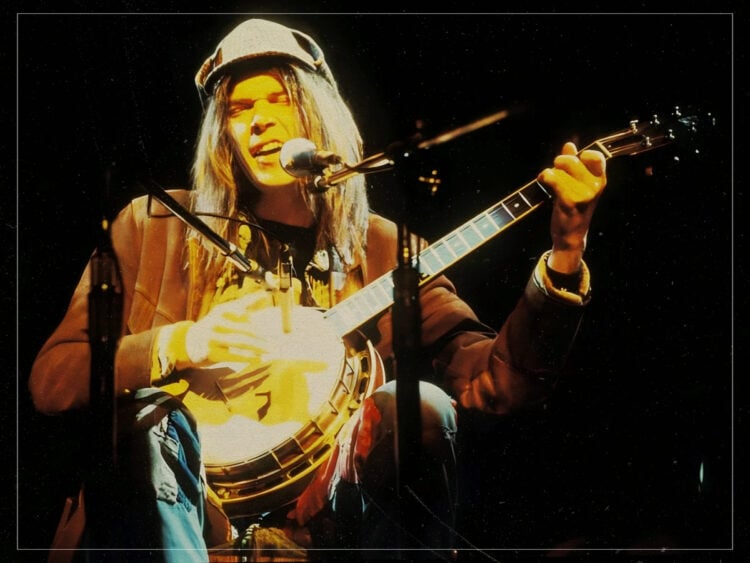

“When you want a song to take off, there is no better band than Crazy Horse. Crazy Horse is a machine; it’s not a passing attraction, it’s not a toy. Grunge was a passing attraction, not the music we play together.”

Neil Young

After all, none of the Seattle bands ever identified themselves as a grunge band, and despite having some true friends from the Pacific Northwest, Young had no problem calling the movement a fad when talking about the power of his own band, saying, “When you want a song to take off, there is no better band like Crazy Horse. Crazy Horse is a machine; it’s not a passing attraction, it’s not a toy. Grunge was a passing attraction, not the music we play together. Crazy Horse was there before the grunge movement, and Crazy Horse survived the grunge.”

That might have been hard for some Seattle bands to hear, but that wasn’t Young trying to offend anyone by making that music. It was only to poke fun at the labels that took one look at someone in a flannel shirt and saw an excuse to print money by signing them. Young was even happy to work with many grunge bands, but seeing it as a passing attraction was probably the best way to see it.

When people started thinking too much about their place in the world, things normally got a little too messy. Grunge represented a glorious return to form for authentic rock and roll, but since Pearl Jam ran from the limelight and Nirvana imploded too early, it’s not like they were aching to be rock stars in the same way that hair bands were.